I’d rather have a Paper Doll to call my own than a fickle-minded real live girl

“Paper Doll” —Lyrics written by Johnny Black 1915, recorded by The Mills Brothers 1942

Get this. The song “Paper Doll” (“when I come home at night she will be waiting, she’ll be the truest doll in all the world”) was composed during WW I and recorded during WW II—two of the more famous international wars of mechanical ferocity—which killed people in great numbers on one hand, and killed chastity in a great number of people on the other—in the western, 20th century disruption of simple, misty, village existence.

The automobile, the cinema. Also hordes of young, robust male soldiers far from home occupying men-depleted foreign towns.

Wars promote murder—and sex.

The man who sleeps with many women, or who desires many women, is not looking for the elusive one, for you don’t need to search for love sexually. The man who sleeps with many women is escaping the heartbreak of losing “the one.” “The one”—love and sex living together in one person.

Men all want one love—after the mother, the wife. All men treasure monogamy with the woman of their dreams.

It is often said humans are not monogamous. This is a falsehood. They are monogamous. They always behave monogamously, even when sleeping around.

The Casanova is a former saint—whose heart was broken by a “fickle-minded real live girl.”

Men, then, are monogamous, and faithful marriage, reflecting what men want, is not a prison, but a paradise.

Unfortunately, war—promoting murder and sex—invades the garden and ruins the dream.

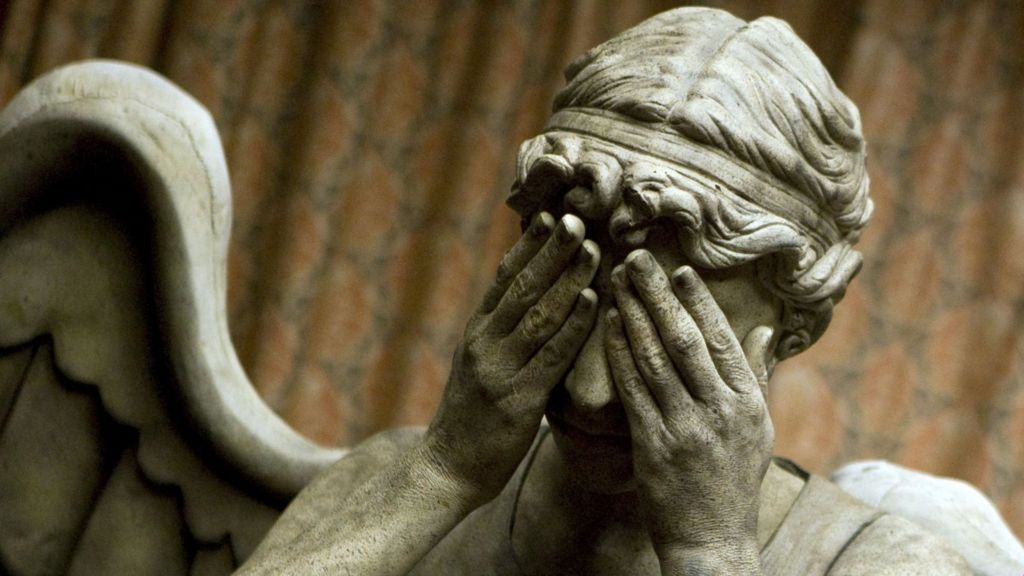

Women, angels who pity and care for men as part of their love for all, mercifully do what they can—to improve the lot of males crushed by circumstance.

Some women genuinely pity males—those males whose ideals have been ruined and who cry out for “paper dolls.”

Or, as we hear in the news today, not “paper dolls,” but “sex robots” (!!) which are said to be just around the corner, if not already here. (!!)

Seductions—by real women, paper dolls, robots, fantasies in the head, or pictures on the wall. It really doesn’t matter. These are merely the effects of the tortured, miserable, heart-broken male.

Women, for the sake of these devastated men, invented Fickle-ism, a set of accepted behaviors in which women get to be fickle, and not virtuous.

Fickle-ism was invented to save men’s pride: “she left you, not because of your shortcomings, but because women are like that—they are fickle, they can’t be true, they sleep around, they have the attention span of a child. So don’t blame yourself. Go ahead and sleep around yourself. Hurt a woman, in turn. It’s okay. People sleep around. They like sex. That’s what they do.”

Fickle-ism soothed the male ego, a male ego crushed by ruined idealism—the belief in faithful marriage and monogamy.

If the ideal—the “woman of your dreams”—is impossible, at least salvage a little pride for those boys, those idealists, those good men, who really did want love, and who have tasted profound despair.

Fickle–ism often goes by another name.

Feminism.

This month two important Feminist Zeitgeist books have arrived on the market:

Camille Paglia, a pro-porn, anti-feminist, warhorse (the genders are different—Rousseau is wrong: nature, not society is the most important trope when it comes to genders—feminism wrongly makes women “equal” to men while at the same time pushing them into danger) has published a new book (a collection of old essays, actually) called Free Women, Free Men: Sex, Gender and Feminism

Laura Kipnis is a film professor at Northwestern, who recently got into some Title IX trouble where she teaches. Her just-released book, Unwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes To Campus, documents today’s “sexual paranoia on campus.” According to Kipnis, women on campus are being turned into helpless victims, into easily-triggered children, and feminism, which seeks to empower women, is, in the name of advancing women’s rights, actually turning back the clock to an era of women as helpless damsels in distress—-and she pins much of the blame on the Department of Education’s hyper-feminist Title IX funding reality (no school will bite the hand that feeds it) expanded to a hyper-sensitive degree in 2011 by the Obama administration.

Kipnis points out that males are fighting back, in court, with lawsuits, against current, repressive, paranoid, feminism in the universities.

Kipnis is a Freudian. She believes in repression as Freud defines it. Taboo sex with siblings and parents is something she’ll explore in her classroom. She admits to sleeping with “a professor or two” as a student. All part of student life, as she sees it.

Kipnis thinks it’s okay for professors and students to have sex.

A male professor at her university lost his job—he got drunk with a female student (who was below the legal drinking age) on an art gallery “date” and the student stressed out afterwards (she ended up at his apartment) and brought a complaint.

Kipnis defends the professor.

The stories by professor and student of what happened on the night in question differ. But both agree they were at a jazz club, at midnight, and they were drunk, and kissing. Kipnis spends a lot of time on minor details of the evening and feels the student lied about some things.

The basic facts, however, clearly point to a professor’s behavior not in keeping with the idea of a university.

It’s a mystery how anyone can condone professors drinking, or sleeping with, students.

Let’s ask: What is a university?

Simply it is this: Professors assigning work and grading students for that work.

There is no university worth the name if professors don’t do this job.

A student may attend college and not do school work. That’s her choice. The university still exists if a student attends, and chooses not to be studious.

But if the professor drinks with the student—what is that? That’s no longer a university. It’s something else. And if a professor has sex with a student? That’s not a university, either. How can a transcript of grades from that university be trusted? How can we trust any grade the professor awards that student?

As a Freudian, Kipnis believes there’s always a danger to forbidding something—you make it more alluring. Perhaps murder (or sleeping with your mother!) has a certain attraction for some, because it’s forbidden—but that’s no reason not to have laws against it.

Kipnis writes that it was not until 2012—very recently—that her school forbid professors from dating students. This is pretty shocking. Should it be okay for professors to date students? Really? And Kipnis doesn’t like the new rule. She thinks college students are old enough to date whom they choose, and that young women should not be treated like vulnerable, helpless creatures. Kipnis, believing herself a good feminist, doesn’t think women need to be protected from men, except, of course, when the man is a criminal rapist.

Paglia is different. She believes all men are rapists at heart. This is how nature made them. Paglia believes women do need to be careful. She believes women are powerful femme fatales with sexual allure. They are not, nor should they try to be, just like men. Paglia laughs at the idea that gender is a social construction. Nature, red in tooth and claw, rules the night, according to Paglia.

On college campuses, the following is definitely on the rise: a woman (often drunk) will sleep with a guy, and then decide he “raped” her, and accuses him—and the guy’s life is destroyed.

Kipnis believe this is what happened to the professor—in the case she examines in her book, Unwanted Advances, the case which she referenced earlier in a Chronicle of Higher Education article—which brought feminist protests against her, fueling the eventual publication of Unwanted Advances. Kipnis is reasonable—she concedes the professor made some poor choices, and can see why the university had to let him go; but she does go to a lot of trouble, a great deal of trouble, it seems, to defend him, and makes the case that a troubled, man-hating, feminist student used the college rules to destroy him.

Kipnis believes the feminists who hate men and cry rape at every chance are out of control. No one would disagree that false cries of rape and abuse are wrong.

As a feminist, Kipnis believes feminism has gone too far, and is making women weak.

Kipnis thinks women should be strong, independent, curious, and ambitious—and sleep and drink with whomever they want.

Paglia would say this is naive.

There are three things at play here.

One, Actual rape, or whatever is objectively and measurably criminal—which everyone condemns.

Two, Sex, and the whole range of regrets, recriminations, doubts and misgivings which might come to light afterwards—and the question of who is having sex with whom.

And finally, Institutional Integrity. Which cannot exist if professors sleep with students.

Number two (Sex)—and, with Kipnis, Number three (Institutional Integrity) is where Fickle-ism, or Feminism strongly gets involved, and tends to mess everything up. Women are feminist—that is, they are fickle. Free and unpredictable. Just like guys.

People tend to be free and unpredictable. Sure. Agreed. But this is not the point. Free to do what? Unpredictable in what ways? Only the context makes the “free” good or bad.

The fickle is never, in itself, good.

To repeat. Women were being good to men when they invented Feminism—or Fickle-ism.

Fickle-ism, as we’ve seen, salvages men’s pride. You got your heart broken? She left you? Don’t feel bad. Women are free agents. Women are not passive flowers for men’s enjoyment. They have their own minds. They are wanton, indecisive, free, and fickle.

But men don’t need this.

Men need to accept it if they are rejected by a woman. There’s always a good reason why. It’s not because women are fickle. Or stupid. Or bad.

Not that men and women will not be fickle sometimes, make bad choices, or make cowardly choices. But when it comes to laws and rules, feminism and fickle-ism should never be a factor. Laws should not promote bad behavior, but good behavior.

Bad people making mistakes and bad choices will always be a problem.

But bad laws are far worse.

Kipnis is correct to push back against the excesses of police-state feminism.

She is utterly wrong, however, to object to the rule which forbids professors from sleeping with students—and therefore her entire argument collapses.

Fickle-ism will tend to do that to any argument.