The following essay is offered as nothing more than an intoxicating drink, with a few unique qualities—most of the musings here you’ve probably heard before; sometimes it’s only emphasis that matters.

Recall the scene in the Meno: Socrates proves all knowledge is recollection (which means the soul is immortal) by suggesting to an unlearned child the means to answer a difficult geometrical problem.

The Platonist poet, Shelley, agrees:

Reason is the enumeration of qualities already known; imagination is the perception of the value of those qualities, both separately and as a whole. Reason respects the differences, and imagination the similitudes of things. Reason is to imagination as the instrument to the agent, as the body to the spirit, as the shadow to the substance.

Knowledge involves a certain humility; humans, the Platonist knows, do not invent; “reason” is merely “recollection,” or, as Shelley puts it, “enumeration of qualities already known.” Qualities are not invented, imagined, or discovered; qualities are, as the (grounded!) Romantic understands, “already known.” And the “imagination,” according to Shelley, “is the perception of the value of those qualities, both separately and as a whole.” Imagination is the “perception of the value of those qualities.” Imagination doesn’t create, or invent; the whole process is far more mundane (says the Romantic!); “perception of value, with an eye to “separately and as a whole.”

This is not easy stuff, but easier, since the Platonist grasps how really modest and small human intelligence is—the “imagination” is the “agent” perceiving the “value of qualities already known,” by using “reason” as an “instrument.”

This intoxicating drink I offer, with a little help from the Romantics, should calm and relax you, if nothing else. Complexity, discovery, labor, be gone.

This is what I intend to do. Give you a whiff of poetry, Christianity, and Neo-Romanticism. You can even close your eyes and find your way.

You know this stuff.

You know it’s true.

But you’ve forgotten.

This essay, “A Few Remarks on Poetry, Christianity and Neo-Romanticism,” should not be taken any more seriously than if flowery letters stating the same should be found on the side of a bottle. When we say seriously, sometimes, what we drink, and the label embellishing it, is serious indeed, but not in the manner of truth, but only of pleasure—so drink, and become intoxicated, and see what pleasures follow; nothing found in this Scarriet essay will necessarily be true; you’ll find only random observations made by a poet for the sake of poetry.

The defense of poetry is, by now, an old practice; half-wits do it; narrowing the subject of poetry to include “Christianity and Neo-Romanticism” is nothing more, really, than an attempt to peak interest in the drink. Philosophy is my beach-reading; if “A Few Remarks” is philosophical, good—think of it as amusement in a philosophical vein.

To state the Neo-Romanticism theme simply: the first criterion of poetry is beauty, in all its particular attributes, heightened by the imagination, and everything else flows from this highest category.

Beauty is advantageous for two reasons—imagination must be present to an extraordinary degree, since imagination first began as the urgent invention to create happiness when faced with sorrow, and beauty is happiness; secondly, beauty also requires harmony, and therefore a certain order and rigor is always necessary to carry off that harmony. Beauty, then, keeps poetry enthusiastic, since happiness is the best motivator for enthusiasm, and at the same time beauty requires expertise and skill to add the necessary harmony to the imaginative attempts to be beautiful.

With Neo-Romanticism, then, beauty is the top category—for the practical reasons just given, and this stricture need not be onerous; beauty was chosen precisely because beauty is not onerous—and naturally, all other elements may of course be present (so modern irritation with the flimsy idealism and ineffectual prettiness of “beauty” does not get the upper hand), just to remember that beauty is the measure and general design which prevails, even as the frightening (with its sublime attributes), the humorous (profound, or sublime wit) and other qualities contribute, in descending order, to that harmonizing effect the Romantic poet is known for, whether it is Byron laughing, Coleridge weeping, Keats gasping, Shelley sighing, Wordsworth philosophizing, Tennyson singing, Millay regretting, Eliot whispering, or Mazer dipping his dreaming toe in the dreaming springs.

Harmony is the leading trait of beauty, and while most poetry refers to things outside of itself to win favor (the poet serving as a kind of rough, honest, social messenger) harmony demands all interest reside within the poem itself (easy political sentiments, in this case, fail) and so how the parts fit is crucial. We know instinctively, but not rationally, how the parts of a beautiful face harmonize to give us pleasure—the trick surpasses our understanding; the same nose on another face is merely a beautiful nose on an ugly face; judgment of the whole is all. The poem cannot refer; its beauty must be its own, and only harmony can achieve this, for ‘a poem’ as it exists as ‘a poem’ is not beautiful; several parts harmonizing is the poem’s only chance.

The poem as a self-enclosed entity is imprisoning—harmony must be freeing, even as it forces parts together to make them fit. Parts must dwell beside each other in interesting and freeing ways, even as they harmonize as a whole—this is the key to beauty. Eyes must be able to flash like stars and be vastly different from mouth, nose, and chin—even as these eyes live on the same beautiful face as those other features: the nose—what can it possibly have to do with the eyes? It’s all a mystery, but certainly not a trivial one, since beauty and harmony are certainly not trivial.

Yet in many respects the harmony of a face is quite simple—and almost without harmony—compared to the harmony of a piece of music, or a poem. All a pretty face needs is: pretty eyes, check, pretty nose, check, pretty chin, check. How do these harmonize? It is not so much harmony, as a mere list of pleasing attributes. More profound and mysterious by far is the notion of the face itself. What is a human face, and why does it please? Then we would need to posit material considerations which have nothing to with lofty notions of beauty and harmony, and yet, these considerations are profound nonetheless: the eyes see, the mouth speaks and tastes, etc. The face is part of a living thing thriving in the world. The beauty of an eye is a poetic idea, since the eye is an instrument for seeing, and yet the seeing action of the eye-instrument is part of its beauty—practical considerations harmonize with beauty.

Harmony is an ever-widening process, even as it belongs to the limits of its action as a harmonizing whole, with a defined beginning, middle, and end.

We must ask, therefore, what practical considerations belong to the poem, as we explore its harmony and beauty. The upper idea hiding a subordinate idea is a crucial way a poem harmonizes, just as a piece of great music allows us to hear different threads simultaneously.

This brings us to Christianity, as it pertains to practical life harmonizing with beauty.

The poet makes choices, in the imagination, to allow us to perceive the more beautiful result. The poet, like the priest, must take practical matters and somehow harmonize them with beauty for the sake of imaginative fancy.

The “virgin birth” is just such an imaginative fancy, which pleases the Christian—but not the atheist, who sneers, “Virgin birth? Bah! Impossible! this absurdity brings down, like a house of cards, your entire religion.”

But the Romantic, who might be an atheist, will, as a poet, nonetheless tell the objecting atheist, “hold my beer.” Is religion not a series of interconnecting ideas, rather than facts?

The “virgin birth” is not a fact, but an idea—an idea which lives in a universe of other ideas; Keats’ “negative capability” defines the poet as one who can entertain doubts, who can temporarily dwell where answers are suspended, so that fancy (imagination) has a chance to build a harmonizing aspect of things, which moves us happily forward into a better reality.

Religion is a poetic, not a factual, response, to the world.

Harmony and imagination is the religious way.

The factual world (virgin births do not occur) is not a poetic one.

Or it is, if God is a poet.

Secularism is the poet (as fact-master) attempting to be God (as fact-master).

Religion posits God as the one true poet.

For virgin births do occur in the factual world.

The universe itself was a virgin birth. No scientist knows how the universe came into existence, and we doubt whether it was made by daddy light and mama darkness, or any other myth the primitive imagination might invent.

Imagination grows and matures with monotheistic religion. The immaculate conception is a profoundly scientific concept. The one universe was born, not by evolution, but in a manner absolutely mysterious and unknown. This is the fact of existence. The religious fancy, the poem, and the scientific fact, come together, in the harmonizing imagination, as one.

The harmonizing relationship between the Old Testament and the New Testament, in which the new obeys, and yet miraculously fulfills, and surpasses, the old, pertains to the strategies of poetry itself, and the inner harmonizing character of poems.

The parts come from the whole, and not the other way around.

God coming to earth requires a virgin birth, since there is no immortal element on earth; there is no immortal dad to impregnate the mortal mother. One needs to hold off the objection, then, to the virgin birth, in order for the God-coming-to-earth story to proceed.

The sacred story of Christ is a great poem, and so feeds poetry, if poetry harmonizes fully, and across the board, and, if we think of the trope of everyone writing the same poem, every time a poet writes a poem, as more than mere linguistic expression, not as a mere fragment of a song or a fragment of a plaint, or a fragment of a protest, or any factual observation the would-be poet might want to indulge in, we can understand a poem as a poem coming into being. And this exists as a cloud of mystery, not as ‘writing poems for Christ,’ or anything so obvious or silly.

A virgin birth also avoids, for aesthetic reasons, sex, the messy core of messy reality. The raw fact of sex is not condemned or avoided, for sex certainly does have its harmonizing place in the world.

But what to do about sex is not a trivial matter, and has profound practical considerations. In The Sound of Music, Julie Andrews must choose whether she wants to be a nun, or not.

Her choice belongs more to religious behavior, than to religious poetry. Religion is in the world, as much as the secular is.

However, we did mention earlier that good harmony keeps its parts, to a certain extent, free from each other. Harmony, which pulls together, should also be freeing. The freedom to choose to be a nun and serve the religion that way, belongs to a profoundly harmonizing challenge.

In another major religion, all women of the religion are forced to be nuns. Here the woman is free of the agonizing moral, social and religious choice which women in the Catholic faith must choose for themselves. Julie Andrews did not know what to do. The West has such a demand for choice and freedom, the whole thing for many people can be overwhelming. But the more freedom, the greater necessity there is for harmony and poetry.

Any religiosity seems horribly quaint in the face of modern, secularist advance. I speak a little of Christianity (of which I am ignorant) just to appease the title, “A Few Remarks on Poetry, Christianity, and Neo-Romanticism.”

Quickly, before I lose all respect, I would like to examine, for pure pleasure alone, a recent sonnet by Ben Mazer, the contemporary Neo-Romantic poet.

A virgin snow remade the world that year.

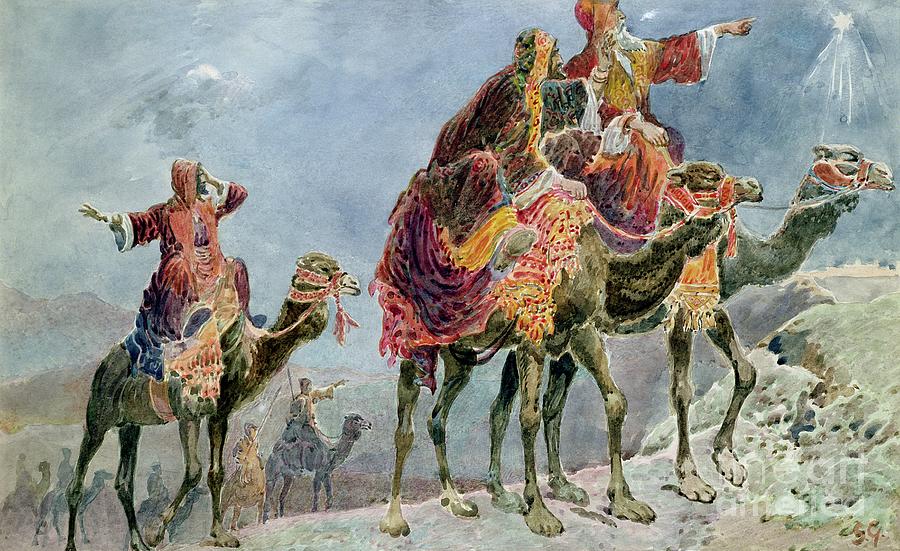

Three kings had heard the rumour from afar

and wandered from the East by guiding star.

The sacred place was frosted with the sheer

anticipation of a world to come.

The shepherds and the animals were dumb

with gazing out the windows for the far

approaching kings, the radiant Hamilcar.

The old world would be disappearing fast;

the marvels that they saw they knew would last.

The wind stood patient on the bare swept sill.

Guests stood in silence on the little hill.

The three kings from a distance could be seen.

It was the most spectacular thing that’s ever been.

The Neo-Romantic aspect of this will be quickly seen. When, against our will, there’s no escape, and we surrender to poetry’s predicament, this is love, romance, and all the helplessness implied, as expressed by again, Shelley, in his Defense of Poetry:

Man is an instrument over which a series of external and internal impressions are driven, like the alternations of an ever-changing wind over an Æolian lyre, which move it by their motion to ever-changing melody. But there is a principle within the human being, and perhaps within all sentient beings, which acts otherwise than in the lyre, and produces not melody alone, but harmony, by an internal adjustment of the sounds or motions thus excited to the impressions which excite them. It is as if the lyre could accommodate its chords to the motions of that which strikes them, in a determined proportion of sound; even as the musician can accommodate his voice to the sound of the lyre. A child at play by itself will express its delight by its voice and motions; and every inflexion of tone and every gesture will bear exact relation to a corresponding antitype in the pleasurable impressions which awakened it; it will be the reflected image of that impression; and as the lyre trembles and sounds after the wind has died away; so the child seeks, by prolonging in its voice and motions the duration of the effect, to prolong also a consciousness of the cause. In relation to the objects which delight a child these expressions are what poetry is to higher objects.

In order for this formula, which Shelley has evoked, to work: the ‘human lyre’ which “seeks, by prolonging in its voice and motions the duration of the effect, to prolong also a consciousness of the cause,” we must first really be a lyre, and be literally ‘played’ as a passive instrument; this passivity is the secret to human joy: settling into a dark theater and allowing images to wash over us as we sit there passively—far removed from drudgery and reason and understanding and work of any kind—one is simply a passive lyre. This is why Poe, ‘the Last Romantic,’ championed poetry which aspired to beauty and music and condemned the didactic poem—for didactic poetry slides over into the realm which belongs to labor and pain, and not thoughtless, passive, joy, the surrender necessary to experience poetry in a state of true excitement.

This is not to say poetry (words) benefits from a darkened theater, but the idea of inescapable focus is the same—poetry is different from film, but their joy is based on the same thing: trusting passivity, which frees us from the irritable ‘reaching’ we normally do, in thought or action, and we think naturally here of Keats’ Negative Capability. Sensuality (sound) in poems works like the brightened screen in the cinema—the sensual, unconscious device of passive joy, used to produce the higher version of harmony which attempts to surpass itself.

If this passive, first, step of delight is not allowed to occur, the next step: “which acts otherwise than in the lyre, and produces not melody alone, but harmony, by an internal adjustment of sounds or motions…” cannot occur.

To intellectualize, in the common light of day, the horrors of the world, in the spirit of a utilitarian lecturer, will deprive poetry of Shelley’s cinematic mission, and will end up on the other side of Neo-Romanticism; this is why prosaic Modernism is so hostile to Romanticism—as Scarriet has demonstrated in a number of articles over the last ten years.

In Part Two, we will examine Mazer’s poem more closely.