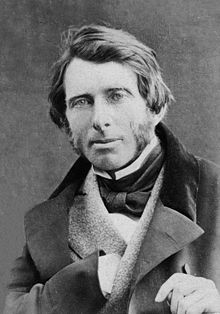

Hybrid, collage portrait. Which has less charm? Modern poetry or modern art?

SCARRIET HAS ELEVATED THE FOLLOWING SCARRIET COMMENT (ON “WHY POETRY SUCKS NOW”) FROM ONE OF OUR READERS (‘MIKE’) TO THIS ARTICLE (WITH OUR REPLY BELOW):

Hey y’all.

As an art school trained painter and a self inflicted poet, I find it interesting to observe the differences between visual art and literature; or more specifically, the difference between drawing and writing.

In visual art (drawing), one is challenged to “represent” what they “see” by way of marks on paper. Initial attempts are typically awful. Continued failure leads to frustration and abandonment, or else the determination to “learn” how do draw. Such learning requires one to engage in the reciprocal activity of practicing drawing “methods” while simultaneously understanding the nature of the visual forms those methods are meant to capture. It is only through this interplay of method and understanding that one can begin to draw what they see.

At which point one realizes the meta-lesson of drawing, which is that nobody draws what they see. You can only draw what you KNOW about what you see. That knowledge… visual knowledge… is not the same as vision. After all, most everyone has two eyes by which to see… but most people cannot draw beyond the primitive. And the reason is that their knowledge of visual forms and methods is (well)… primitive.

A further implication is that the drawing (as art object) is not equivalent to the visual perception of the subject matter of the drawing. In other words, a drawing of an apple is not an apple. The drawing is a representation only… a mental construct… a methodological translation of visual perception via the artistic form of a drawing.

All of this might seem terribly boring and inapplicable to the subject at hand. But if you indulge me for another minute… and lay your egos aside… then maybe I can make my point. Which is this. I have never gotten the impression that writers consider writing to be a “methodological translation” of (let’s say) interior thoughts and feelings, into the artistic form of the written word.

I think the reason for this is that we are all able to speak and write with some proficiency from an early age. I could also include the activity of contemplating ideas in our minds, and of subconscious processes… which we (kind-a) assume to be language based. These very powerful tools (thinking, reading, writing, speaking) allow us to think and imagine VERY GREAT things. Yet when we attempt to write it down… it’s not so easy. And this is no different from the artist… who might peer out into some beautiful landscape and be filled with desire to represent what he perceives and feels, yet be unable to do so. But whereas the artist is forced to reconcile his failures with the need to learn a method and to grasp the nature of visual form (as a translation between vision and representation)… I wonder if writers see their failure in these same terms.

Or does the writer simply “work harder”… or “write what they know”… or “keep plugging away”… or “writer’s write”… or “never give up”…. or a thousand other ways to say the same thing… admonishments to pound away at reality… that somehow representations will condense NOT out of understanding, but of somehow aligning the monkeys in our brains to coincidentally type out the works of Shakespeare. But just as a drawing is not the hand’s record of the light striking your retina… the written word is not a passive record of the mind’s ability to cogitate and speak out loud. But I wonder if writers know this? Or does the immediate accessibility of language mask the distinction?

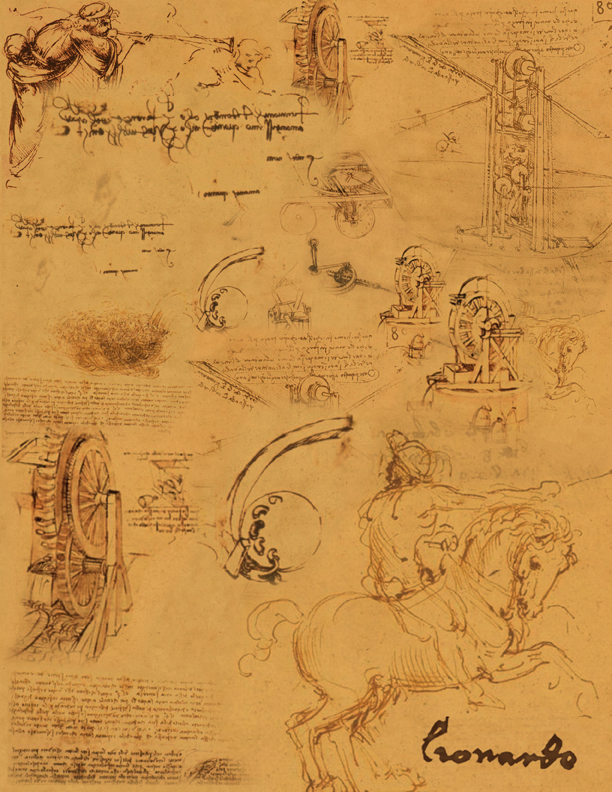

Another aspect of this distinction is that in the visual arts, the impact of artistic theories are well understood, and are considered to be highly relevant. In fact, any good art school program is going to require a thorough grounding in the history of art from ancient times to the present day. This is an enormous investigation into cultural history. Artists are meant to take such things very very seriously, and are meant to understand that the nature of artistic method and form and meaning derive from such cultural moments as have occurred over time.

But I have to wonder if writers think of writing in the same way. For instance… do writers ever wonder about the writing skills of ancient Egyptians? Because artists are very aware of the art of ancient Egypt.

Visual artists are taught to understand that ancient architectural forms are rooted in archetypical associations that the human species has evolved from out of their prehistory. Are there any analogous ideas that writers possess about their own artistic heritage? Are writers schooled in the social and artistic shifts underlying the sea-change of the Late Gothic transition to the early Renaissance? Visual artists sure are. In fact, they make Pilgrimages to Rome and Florence and Venice just to lay their eyes on the art… to sit under the sun and absorb the aura of history, and thereby to connect with the meanings of these things. Do writers do such things? Or are words just words and everyone has them and all you need to do is pound away at a typewriter until it just pops out of you? Is writing like a piano… a music making machine that you only need whack at until a tune emerges? And when it does, you claim it as your own, and marvel at the mystery of your own origin… and try not to consider that it might all be happy accidents and the accommodating of the random.

I don’t mean to sound cruel, but I think that writers have no sense of these things, or of writing as an activity distinct from the basic language skills of talking and thinking and jotting stuff down. In truth, most visual artists don’t give a damn about the things I’ve waxed on about. The difference is this… that they are supposed to… whereas writers have no such presumption built into their activity.

And so it should come as no surprise that when poetry falls victim to the ravages of modernist or post- modernist theories of everything… that writers should twist in the wind and wonder what the hell is gone wrong. But such things are no surprise to visual artists, who only need look around and see all the crap contemporary art floating about the world. We see it everyday too. But at least we know what it is, and why it is. Because we are trained to know these things. Because art comes out of theories and methods… not out of the naive ability to speak words and have thoughts. Bad theories and absent methods lead to the destruction of art. The alternative isn’t to abandon ideas, but to understand that good ideas must be asserted. In the visual arts, such advocacy is mistakenly assumed to be a return to the art of the past… to neo-classical style paintings of nudes and heroic figures in togas. Which is ridiculous. But this is no different a mistake than when some poets try to defeat bad post-modern poetry by adopting the writing styles of Chaucer and Shakespeare.

The history of any art does not exist to be mindlessly rejected or mindlessly copied. What good can come out of mindlessness? It exists as a repository of ideas from which some meaningful “next thing” might emerge. Who knows what it is. I try to make this point to visual artists… but nobody seems to give a damn. So now I’m making it here in this poetry blog. And this is an uphill battle I suppose, because writers are not trained like visual artists, and they may not be aware of what they are really trying to do. So maybe writers should stop screaming about bad poems, and begin instead the difficult task of understanding the nature of the writer word at all.

SCARRIET RESPONDS

One of the Scarriet editors works at a large, urban, liberal arts university (once a teacher’s college), which recently acquired an art school; Scarriet covers not only the decline of poetry, but how art, poetry and philosophy mingle, so you can imagine our excitement at finding this learned and lengthy comment on our “Why Poetry Sucks Now” post, a delightful comment which Scarriet has elevated to a post of its own.

“Art comes out of theories and methods…not out of the naive ability to speak words and have thoughts.”

So says the “art school trained painter,” who reminds us that “nobody draws what they see…they only draw what they KNOW about what they see…visual knowledge is not the same as vision…” and “do the writers know this?” Further: artists know art is a “methodological translation” of reality, where writers, by comparison, seem to be mere “passive” (and random!) recording devices of what is universally accessible to all: language.

We agree entirely with the gist of this, and though we are a writer, not a painter, we feel no insult at all, and we are illuminated by the truth of what this painter has—written.

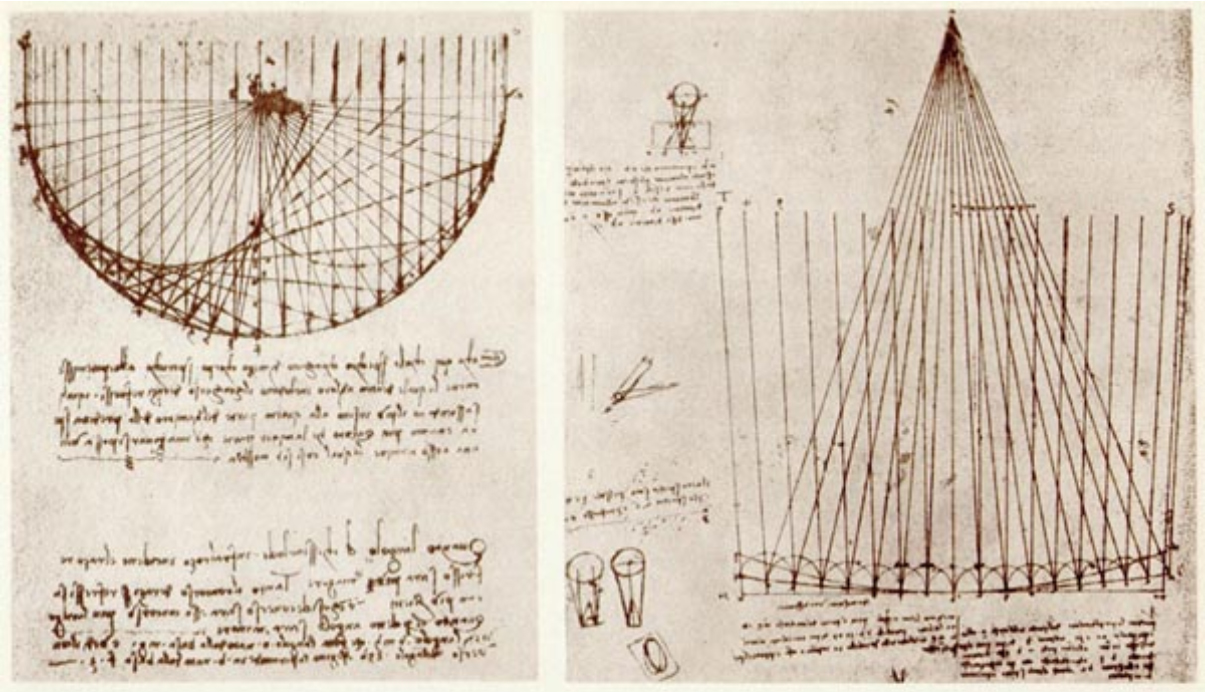

The truth of painting’s superiority to writing was put most forcefully by da Vinci, who said the experience of the eye is the beginning and proof of all science: discontinuous quantity (arithmetic), continuous quantity (geometry) and perspective the holy trinity of astronomy and all human knowledge—painting as the body, poetry merely its shadow. Body (substance and its measurement) trumps Blah Blah Blah. Absolutely.

However, there is a “writing method” tradition—embodied in full by Edgar Poe (unfortunately not taught in writing programs) who we never tire of quoting; the following, from the Master, reflects the thinking of our art school trained painter:

There is a radical error, I think, in the usual mode of constructing a story. Either history affords a thesis—or one is suggested by an incident of the day—or, at best, the author sets himself to work in the combination of striking events to form merely the basis of his narrative—designing, generally, to fill in with description, dialogue, or authorial comment, whatever crevices of fact, or action, may, from page to page, render themselves apparent.

I prefer commencing with the consideration of an effect. Keeping originality always in view—for he is false to himself who ventures to dispense with so obvious and so easily attainable source of interest—I say to myself, in the first place, “Of the innumerable effects, or impressions, of which the heart, the intellect, or (more generally) the soul is susceptible, what one shall I, on the present occasion, select? Having chosen a novel, first, and secondly a vivid effect, I consider whether it can best be wrought by incident or tone—whether by ordinary incidents and peculiar tone, or the converse, or by peculiarity both of incident and tone—afterward looking about me (or rather within) for such combinations of event, or tone, as shall best aid me in the construction of the effect.

Poe rigorously asserts the secret of all composition—and all morals: in the beginning (the intention) we discover our end (the effect)—and the myriad details, of drawing or writing, fall into place, or should fall into place, in the execution. By this method, these are eliminated: The random, the details which overwhelm, and self-indulgence.

The point our painter makes in his comment—that we draw what we know about what we see, not what we see—is, we feel, a reiteration of Poe’s method, and here an important point about ‘knowing’ should be made.

The separation between knowing and seeing does not exist because seeing needs correcting or is insufficient—the natural seeing humans do reflects nature’s efficiency: perspective which makes distant objects small, for instance, is the perfect solution to the over-crowding of the visual field: and understanding perspective is an understanding which is not distinct from seeing, but is the same as seeing: the “knowing” the artist is engaged in is nothing more than a selecting, a framing, a focusing—and not something superior to seeing; it is the very same thing Poe refers to when he says, “Of the innumerable effects, or impressions…which one shall I, on the present occasion, select?”

Here is the vital point: the distinction which our art school trained painter makes between vision and visual knowledge is different than we suppose: “visual knowledge” is not something which stands above and apart from “vision;” quite the opposite: vision is the whole, visual knowledge is the part, of the whole thing. Vision is natural and perfect, visual knowledge is imperfect and contingent. Visual knowledge is the narrow “effect,” of which vision is the cause, and the connection between visual knowledge and vision is seamless. All training, all knowledge, is nothing more than focus: both the artist and the writer do not see more; they see less than the layperson; all knowledge is knowledge of what to ignore: what not to see, what not to write, what not to draw.

Modern poetry errs in making poetry subordinate to prose-ideas; modern art errs in making painting subordinate to collage-ideas.

The answer is not simply, “less is more,” but how (to what end) does the artist make less more?

Plato (and who cares if he wore a toga?) is another thinker who tells us that vision (reality) trumps visual knowledge (art), since vision is the true knowledge of which visual knowledge (art) attempts to unfairly usurp—not because knowledge should not be trusted, but because knowledge is not what we think it is: the vision IS the knowledge, the vision (reality) contains far more perfectly and ultimately the knowledge, of which art-knowledge (and writing-knowledge) slyly hides—especially if the untrustworthy student falls in love with representation, illusion, and dream passionately spun by the sophist for all sorts of partially realized reasons dripping with bad taste.

The “methodological” in our art school painter’s “methodological translation” of reality contains two simple things: first, the focus, or selection, we just discussed above (the selective nature of reality informing the selective nature of human vision) and second, the good. We finally want to do good, to produce good, to have a good effect, and here, of course, we refer to Plato’s ‘the good,’ which has other names: justice, happiness, beauty.

Things go haywire when the hubris of human knowledge thinking itself superior to natural seeing, sensing, and feeling takes precedence. “I’m not drawing what I see!” cries the sophisticated painter, “I’m working within specialized knowledge!” Ah, so this is why your painting is bland, trivial, confusing, with lines and colors leading nowhere, a hybrid collage of no real purpose. And the poet who writes poetry which rambles incoherently, having no coherence or lasting interest, is mistakenly certain in that human knowledge which is entirely separate from the effect the poem is actually having. This error arises from the belief that “visual knowledge” is superior to “vision.”

But the objection might come: No! The ‘good’ resides in human knowledge, in human attempts at it, not in simple vision, not in haphazard, unadorned reality, not in nature, red in tooth and claw. You wrongly assume that “this is the best of all possible worlds” and that to merely copy the beautiful and perfect world is enough, and no ideas are necessary; you say the real method is to simply frame part of (what is called by you) “reality.” No, sorry.

But this objection misses several important points: Vision, as it operates everywhere, is efficient and remarkable, and is not the same as “nature, red in tooth and claw.” This is to confuse reality with our special feelings about it. Reality is not “unadorned” or “simple,” and copying it is never simple. “Copying” reality is a highly complex endeavor—our art school trained artist puts it succinctly: “most everyone has two eyes to see, but most people cannot draw beyond the primitive.” Exactly. Human pride believes the complexity resides in the imposition of method, when true method copies nature with da Vinci’s open eyes.

The artist and the poet are finally united by the philosophy which begins with an effect—a design guided by the morality of justice/beauty in terms of what scientifically the senses, as senses, understand, measure, and know.

.

.