SIXTY FOUR ISOLATED, INTRIGUING PASSAGES FROM ALL GENRES COMPETE!

EAST BRACKET

- Anton Chekhov v. 16. Helen Whitman

- F.T. Marinetti v. 15. Stephen Davis

- Marc Andreessen v. 14. Camille Paglia

- Brian Wilson v. 13. Eric Singer

- Paul Simon v. 12. Edgar Poe

- John Updike v. 11. Travis Kelce

- Sharon Olds v. 10. Taylor Swift

- Steven Cramer v. 9. Nathaniel Hawthorne

- Nathaniel Hawthorne

- Taylor Swift

- Travis Kelce

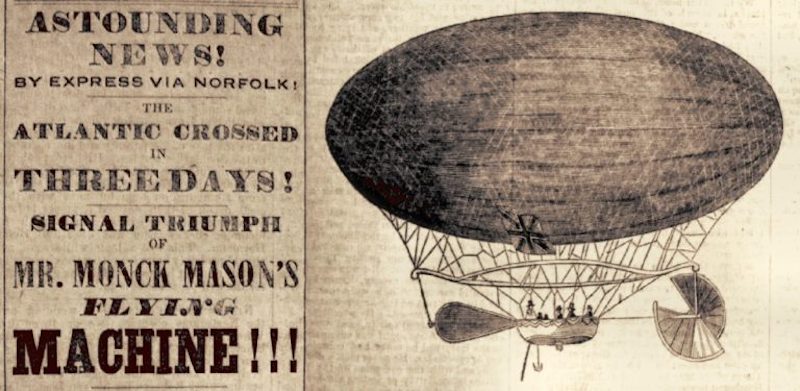

- Edgar Poe

- Eric Singer

- Camille Paglia

- Stephen Davis

- Helen Whitman

Life, unfortunately, is random, and the way life is ordered makes a mockery of itself, such that those who try and present it, and live it, in all its variety, are doomed themselves to be less interesting than those who present it and understand it from an extremely narrow perspective—these are the “highly skilled” we tend to admire for their “expertise” and who participate in a “craft” or a “guild” which has its own rules and reason for existing, and repeats that narrowness in order to fulfill itself. What distinguishes one craftsman from another in any given field is narrower still, and the preference for one over the other is the basis of all that is crazy and insulting about love—we have a “favorite” who is essentially the same as his or her neighbor—the preferment participating in the narrowness of the perception, which is by the devotee’s own definition and understanding, subtlety and taste, the unique flower which is the end of expertise itself, the pearl, we might say, which exists because it irritates the oyster. We are a “fan” of one player or musician or team in a given sport, one we choose over the others—even as an outsider sees them as virtually the same. This tension between the outsider’s “normal” perception and the devotee’s more subtle one is the basis of all human behavior and thought. The hockey fan is passionate about the difference between one team and another or one player and another, while a stranger to the sport sees a world of similarity—guys in hockey player uniforms skating and wielding sticks. The “fan” is obligated to understand differences and is an “expert” insofar as each minute difference to the “fan” is apparent. But love is blind—the fan judges crudely and passionately. They know a great deal, but their “expertise” is finally opinion, preferential in nature; it is not true expertise; it is not based on real experience—which belongs to the favorite player who is actually “good” at playing the sport—and this “goodness” participates in what is narrower and subtler, still. The angle necessary for a good hockey shot, etc.

So the poetry lover participates in this favoritism; and so does the philosopher; so do we all, but never generally, where we can all see each other, clearly, at once, but only secretly and privately and competitively within chosen fields of endeavor which all contain endless trapdoors of narrowness and expertise that finally die in a betrayal of plainness, irrelevance, and similarity.

So it is with this year’s March Madness, which runs the risk of wordiness, since every genre of words is included, and no participant has any particular reason to exist beside its neighbor. The idea of category defeats itself. The idea of category cannot overcome being categorized. There is too much transparency and not enough secrecy. The well-read person has no expertise. This March Madness has no Madness—it conjures up rebounds without walls, shouts without echoes.

Life is random. But to admit this is to cease to exist. The true meaning of the Scarriet March Madness 2024 East Bracket list of items is profoundly similar to the “real” March Madness playing out on basketball courts across America. The only difference is that the field here is wider, and therefore prohibitively random—even if only in our minds.

Read these. All 16. This is a sample of what is available to me in my home library. Nothing is more important to the civilized person. Do not be confused. The list features difference which is not narrow enough to seem real. Yes, it’s a total illusion. A civilized one.

Anton Chekhov 1860-1904 (“A Visit To Friends” Norton Anthology of Short Fiction, 1978)

Her continual dreams of happiness and love had wearied her, she could no longer hide her feelings, and her whole posture, the brilliance of her eyes, her fixed, blissful smile, betrayed her sweet thoughts. As for him, he was ill at ease, he shrank together, he froze, not knowing whether to say something so as to turn it all into a joke, or to remain silent, and he was so vexed, and could only reflect that here in the country, on a moonlit night, with a beautiful, enamored, dreamy girl so near, his emotions were as little involved as on Malaya Bronskaya Street—clearly this fine poetry meant no more to him than that crude prose. All this was dead: trysts on moonlit nights, slimwaisted figures in white, mysterious shadows, towers and country houses and “types” like Sergey Sergeich, and like himself, Podgorin, with his chilly boredom, constant vexation, his inability to adjust himself to real life, inability to take from it what it had to offer, and with an aching, wearying thirst for what was not and could not be on earth.

F.T. Marinetti 1876-1944 (Futurist quoted in “The Despots of Silicon Valley” by Adrienne LaFrance in the Atlantic March 2024)

We are not satisfied to roam in a garden closed in by dark cypresses, bending over ruins and mossy antiques… We believe that Italy’s only worthy tradition is never to have had tradition. Beauty exists only in struggle. There is no masterpiece that has not an aggressive character. Poetry must be a violent assault on the forces of the unknown, to force them to bow before man.

Marc Andreessen 1971- (The Techno-Optimist Manifesto 10/16/2023)

We are told that technology takes our jobs, reduces our wages, increases inequality, threatens our health, ruins the environment, degrades our society, corrupts our children, impairs our humanity, threatens our future, and is ever on the verge of ruining everything. We are told to be angry, bitter, and resentful about technology. We are told to be pessimistic. The myth of Prometheus – in various updated forms like Frankenstein, Oppenheimer, and Terminator – haunts our nightmares. We are told to denounce our birthright – our intelligence, our control over nature, our ability to build a better world. We are told to be miserable about the future.

… We believe in adventure. Undertaking the Hero’s Journey, rebelling against the status quo, mapping uncharted territory, conquering dragons, and bringing home the spoils… We believe in nature, but we also believe in overcoming nature. We are not primitives, cowering in fear of the lightning bolt. We are the apex of the predator; the lightning works for us.

Brian Wilson 1942- (“Caroline, No” Track 13, Pet Sounds 1966)

Where did your long hair go?

Where is the girl I used to know?

How could you lose that happy glow?

Who took that look away?

I remember how you used to say

You’d never change but that’s not true.

Oh Caroline, you

Break my heart.

I want to go and cry.

It’s so sad to watch a sweet thing die.

Oh, Caroline why?

Could I ever find in you again?

The things that made me love you so much then?

Could we ever bring ’em back once they have gone?

Oh, Caroline, no.

Paul Simon 1941- (“Cloudy” Track 3, Parsley, Sage, Rosemary, and Thyme 1966)

Cloudy,

The sky is gray and white and cloudy.

Sometimes I think it’s hanging down on me

And it’s a hitchhike a hundred miles,

I’m a rag-a-muffin child,

Pointed finger-painted smile,

I left my shadow waiting down the road for me a while.

Cloudy,

My thoughts are scattered and they’re cloudy,

They have no borders, no boundaries,

They echo and they swell,

From Tolstoy to Tinker Bell,

Down from Berkeley to Carmel,

Got some pictures in my pocket and a lot of time to kill,

Hey sunshine!

I haven’t seen you in a long time.

Why don’t you show your face and bend my mind?

These clouds stick to the sky

Like a floating question, why?

And they linger there to die.

They don’t know where they are going

And, my friend, neither do I

Cloudy.

Cloud-dee-ee.

Cloudy.

John Updike 1932-2009 (Review of Memories of My Melancholy Whores by Gabriel Garcia Marquez 2005, in Due Considerations, Essays and Criticism 2007)

The works of Gabriel Garcia Marquez contain a great deal of love, depicted as a doom, a demonic possession, a disease that, once contracted, cannot be easily cured. Not infrequently the afflicted are an older man and younger woman, hardly more than a child. In One Hundred Years of Solitude (English translation 1970), Aureliano Buendia visits a very young whore: “The adolescent mulatto girl, with her small bitch’s teats, was naked on the bed. Before Aureliano sixty-three men has passed through the room that night. From being used so much, kneaded with sweat and sighs, the air in the room had begun to turn to mud. The girl took off the soaked sheet and asked Aureliano to hold it by one side. It was as heavy as a piece of canvas. They squeezed it, twisting it at the ends until it regained its natural weight. They turned over the mat and the sweat came out of the other side.” Aureliano does not take advantage of her overexploited charms, and leaves the room “troubled by a desire to weep.” He has—you guessed it—fallen in love.

Sharon Olds 1942- (from “His Birthday” p. 160 Balladz 2022)

When I’m in New York and he’s in New Hampshire, and I’m starting to make love to myself, on his birthday, I look around for something silky, as I’d rubbed the satin binding of my childhood blanket when I’d sucked my thumb to sleep, until I was 13 and had buck teeth. On his 75th, I wanted to caress myself through something which had a glimmery feeling. And when I came, the first time, it almost picked me up and threw me off the bed. Resting, I panted, like the pleasure-wounded. […]

Steven Cramer 1953- (“I Want That” p. 12 Listen 2020)

As I lay down too tired to believe

is a line I love by Laura Jensen.

I imagine it coming to her quickly

like dictation, like cold with snow.

I want that. How I want that.

And the night I believed I sat

in a chair in the middle of the sea

and yet could see the shoreline:

lights, dune grass, a hut, and bluffs

behind them bright, as if on fire—

Oh, I want them, I want them

back like the waterfall a child built

of cheesecloth, papier-mache, wire.

I called it Salishan, a name sounding

like silver buffed up to a shine.

I want that shine too; a ton of it.

I brush my hand across rough cotton

here, or here. And notice, if I’m naked,

the pelt of shower water against my skin,

the scent of scentless soap, the weight

my feet confer to the tub floor. Today

I’ll amble through the city’s jazz of rain.

And the voice beneath my scalp that says

there’s little to no point? Poor voice.

Nathaniel Hawthorne 1804-1864 (“Wakefield” in The Celestial Railroad and Other Stories 1980)

In some old magazine or newspaper I recollect a story, told as truth, of a man—let us call him Wakefield—who absented himself for a long time from his wife. The fact, thus abstractedly stated, is not very uncommon, nor—without a proper distinction of circumstances—to be condemned either as naughty or nonsensical. Howbeit, this, though far from the most aggravated, is perhaps the strangest instance on record of marital delinquency; and, moreover, as remarkable a freak as may be found in the whole list of human oddities. The wedded couple lived in London. The man, under pretense of going on a journey, took lodgings in the next street to his own house, and there, unheard of by his wife or friends, and without the shadow of a reason for such self-banishment, dwelt upwards of twenty years. During that period, he beheld his home every day, and frequently the forlorn Mrs. Wakefield. And after so great a gap in his matrimonial felicity—when his death was reckoned certain, his estate settled, his name dismissed from memory, and his wife long, long ago, resigned to her autumnal widowhood—he entered the door one evening, quietly, as from a day’s absence, and became a loving spouse til death.

Taylor Swift 1989- (“Out of the Woods,” track 4 1989 2014) Jack Antonoff, co-writer

Looking at it now,

It all seems so simple,

We were lying on your couch,

I remember,

You took a Polaroid of us,

Then discovered,

The rest of the world was black and white,

But we were in screaming color,

And I remember thinking,

Are we out of the woods yet? Are we out of the woods yet?

Are we out of the woods yet? Are we out of the woods?

Are we in the clear yet? Are we in the clear yet?

Are we in the clear yet, in the clear yet? Good!

Are we out of the woods yet? Are we out of the woods yet?

Are we out of the woods yet? Are we out of the woods?

Are we in the clear yet? Are we in the clear yet?

Are we in the clear yet, in the clear yet? Good?

Are we out of the woods?

Looking at it now,

Last December,

We were built to fall apart,

And fall back together.

Your necklace hanging from my neck,

The night we couldn’t quite forget,

When we decided, we decided

To move the furniture so we could dance,

Baby, like we stood a chance.

Two paper airplanes flying, flying, flying

And I remember thinking,

Are we out of the woods yet? Are we out of the woods yet?

Are we out of the woods yet? Are we out of the woods?

Are we in the clear yet? Are we in the clear yet?

Are we in the clear yet, in the clear yet?

Are we out of the woods yet? Are we out of the woods yet?

Are we out of the woods yet? Are we out of the woods?

Are we in the clear yet? Are we in the clear yet?

Are we in the clear yet, in the clear yet?

Are we out of the woods?

Remember when you hit the brakes too soon?

20 stitches in a hospital room.

When you started crying, baby, I did too,

But when the sun came up, I was looking at you.

Remember when we couldn’t take the heat?

I walked out, I said, “I’m setting you free”

But the monsters turned out to be just trees.

When the sun came up, you were looking at me.

You were looking at me, oh,

You were looking at me.

Travis Kelce 1989- (speech, Kansas City Chiefs victory parade, 2024)

Oh oh uhhhh. (Kansas City Chiefs Tomahawk Chop chant drunkenly slurred)

Blame it all on my roots!

I showed up in boots!

And ruined the 9ers (your black tie) affair.

The last one to know!

We were (I was) the last ones to show!

We were (I was) the last ones they (you) thought they’d (you’d) see there.

And I saw the surprise!

And the fear in their (his) eyes!

Took their (his) glass of champagne—

Pat took that glass of champagne—

And I toasted you!

What I never knew—what?

—mike removed

(Said “honey, we may be through”

But you’ll never hear me complain

‘Cause I’ve got friends in low places

Where the whiskey drowns

And the beer chases my blues away

And I’ll be okay

I’m not big on social graces

Think I’ll slip on down to the oasis

Oh, I’ve got friends in low places)

(Songwriters: Dewayne Blackwell / Earl Lee, from “Friends in Low Places”

Garth Brooks 1990)

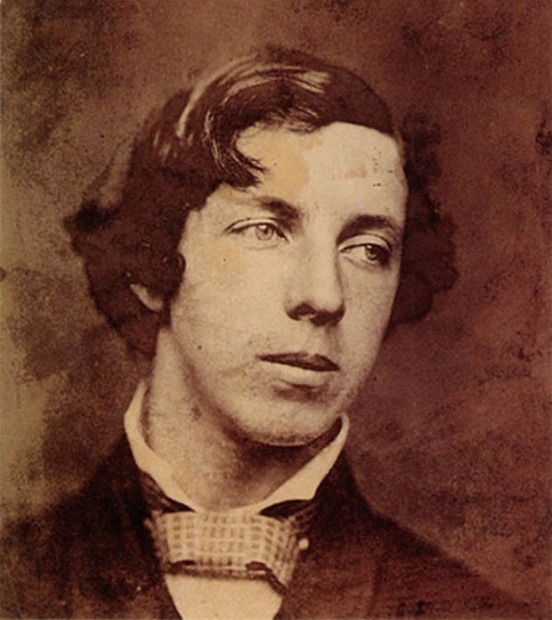

Edgar Poe 1809-1849 (“The Fall of the House of Usher” Selected Writings of Edgar Allan Poe, 1956)

I had learned, too, the very remarkable fact, that the stem of the Usher race, all time-honored as it was, had put forth, at no period, any enduring branch; in other words, that the entire family lay in the direct line of descent, and had always, with very trifling and very temporary variation, so lain.

Eric Singer 1896-1969 (A Manual of Graphology, p. 50 1969)

Finally, the forger who copies another person’s handwriting has to do it slowly. Often the only sign by which the forgery can be detected is found in comparing the reproduction with the quickly written original. The speed of handwriting therefore becomes the decisive factor in ascertaining the genuineness and spontaneity of all the other signs of handwriting; it is the most important branch of study for the expert graphologist, who has to deal in court with disguised or forged handwriting. As spontaneity and a tendency to be calculating are both present in most human minds you will find signs both of speed and of slowness in most handwritings.

Camille Paglia 1947- (Sex, Art, and American Culture, p. 210, 1992)

I will argue that the French invasion of academe in the Seventies was not at all a continuation of the Sixties revolution but rather an evasion of it. In Tenured Radicals, which treats trendy showboating professors with the irreverence they deserve, Roger Kimball makes one statement I would correct: he suggests the radicals of the Sixties are now in positions of control in the major universities. He is too generous. Most of America’s academic leftists are no more radical than my Aunt Hattie. Sixties radicals rarely went on to graduate school; if they did, they often dropped out. If they made it through, they had trouble getting a job and keeping it. They remain mavericks, isolated, off-center. Today’s academic leftists are strutting wannabes, timorous nerds who missed the Sixties while they were grade-grubbing in the library and brown-nosing the senior faculty. Their politics came to them late, secondhand, and special delivery via the Parisian import craze of the Seventies. These people have risen to the top not by challenging the system but by smoothly adapting themselves to it. They’re company men, Rosencrantz and Guildensterns, privileged opportunists who rode the wave of fashion. Most true Sixties people could not and largely did not survive in the stifling graduate schools of the late Sixties and early Seventies.

Stephen Davis 1947- (Old Gods Almost Dead p.227, 2001)

Brian was back in court on Tuesday, December 12, to appeal his drug conviction. Three psychiatrists testified that he was “an extremely frightened young man” and “a very emotional and unstable person.” A sympathetic judge commuted his jail time to three years’ probation and a 1,000-pound fine, provided he continue to seek treatment. Mick and Keith came to court to support Brian, who left after the judgment to have some rotten teeth pulled. Two days later, stoned on downers, he collapsed in his new flat in Chelsea and wound up in the hospital. At a press conference around this time, Mick let fly at Brian. “There’s a tour coming up, and there’s obvious difficulties with Brian, who can’t leave the country.” He talked about how the Stones wanted to tour Japan, “except Brian, again, he can’t get into Tokyo because he’s a druggie.” Some people around the Stones were appalled by Mick’s callousness toward Brian. They wondered why Mick saw him as such a threat. Spanish Tony Sanchez, working now for Keith as a drug courier, thought it was because Brian lived the life that Mick only pretended to live. “Brian was genuinely out of his skull on drugs most of the time, while Mick used only minuscule quantities of dope because he worried that his appearance would be affected. Brian was into orgies, lesbians, and sadomasochism, while Jagger lived his prim, prissy, bourgeois life and worried in case someone spilled coffee on his Persian carpets.”

Helen Whitman 1803-1878 (“To Edgar Allan Poe” Great Poems by American Women, 1998)

If thy sad heart, pining for human love,

In its earth solitude grew dark with fear,

Lest the High Sun of Heaven itself should prove

Powerless to save from that phantasmal sphere

Wherein thy spirit wandered, —if the flowers

That pressed around thy feet, seemed but to bloom

In lone Gethsemanes, through starless hours,

When all who loved had left thee to thy doom, —

Oh, yet believe that in that hollow vale

Where thy soul lingers, waiting to attain

So much of Heaven’s sweet grace as shall avail

To lift its burden of remorseful pain,

My soul shall meet thee, and its Heaven forego

Till God’s great love, on both, one hope, one Heaven bestow.