WEST BRACKET

- St. Augustine v. 16 Graham

- Pirandello v. 15 Ransom

- Richards v. 14 Blackmur

- McCartney v. 13 Michelangelo

- Allen v. 12 Shakespeare

- Peacock v. 11 Keats

- Klavan v. 10 Bryant

- Milton v. 9 Aristotle

- Aristotle

- Bryant

- Keats

- Shakespeare

- Michelangelo

- Blackmur

- Ransom

- Graham

Sport goes about its ignorant business in the nether region between art and war; sport is closer to war—there is a “winner” in both. Art has no “winner” and wants nothing to do with “winning,” and therefore sports and art are oil and water. War is “winning at all costs”—and the question of what “all costs” entails brings philosophy to the table; is it inevitable that sports is “winning at all costs,” too? Many suspect that sports is a racket; that it’s fixed—but none could really enjoy sports if they really believed this, so most don’t believe this, even if they suspect it’s true. “Winning” is always true in war—but “winning” may not be truly “winning” in sports—if cheating and manipulation is at the bottom of it. Art stands apart from the “winning” business; but just as philosophy is reluctantly dragged in to settle the dispute—how much is sports a “winning at all costs” enterprise?—art is made a part of the equation; there is an “art” to winning; there is an “art” to cheating; what is art, if not the ability to idealize “winning” so that no one gets hurt and no one really “loses?” “Ruby Tuesday,” was written by “Mick Jagger.” But no, it was not. In the war of art, Mick Jagger won and Brian Jones lost. As T.S. Eliot has said, one can enjoy Dante without being a Catholic—the angels do not have to “win.” In art, the spoils can go to the devil.

St. Augustine 354-430 (De Civitate Dei contra Paganos The City of God against the Pagans)

Si mundus vult decipi, decipiatur

If the world will be deceived, let it be deceived.

Luigi Pirandello 1867-1936 (letter, 1913) Whoever has understood the game can no longer be deceived; but whoever can no longer be deceived can no longer enjoy the taste or pleasure of life. My art is full of bitter compassion for all those who deceive themselves; but this compassion cannot fail to be followed by the savage derision of the destiny which condemns man to deception.

Keith Richards 1943- Brian Jones 1942-1969 Bill Wyman 1936- officially Jagger-Richards (“Ruby Tuesday” B side single, Rolling Stones 1967)

She would never say where she came from.

Yesterday don’t matter if it’s gone.

While the sun is bright,

Or in the darkest night,

No one knows, she comes and goes.

Don’t question why she needs to be so free.

She’ll tell you it’s the only way to be.

She just can’t be chained

To a life where nothing’s gained

And nothing’s lost, at such a cost.

Goodbye, Ruby Tuesday

Who could hang a name on you?

When you change with every new day

Still, I’m gonna miss you

“There’s no time to lose, ” I heard her say

Catch your dreams before they slip away.

Dying all the time,

Lose your dreams and you will lose your mind.

Ain’t life unkind?

Paul McCartney 1942- (“Eleanor Rigby” Track 2, Revolver 1966)

Eleanor Rigby,

Picks up the rice in the church where a wedding has been,

Lives in a dream.

Waits at the window,

Wearing the face that she keeps in a jar by the door.

Who is it for?

All the lonely people.

Where do they all come from?

All the lonely people.

Where do they all belong?

Father McKenzie,

Writing the words of a sermon that no one will hear,

No one comes near.

Look at him working,

Darning his socks in the night when there’s nobody there.

What does he care?

Eleanor Rigby,

Died in the church and was buried along with her name.

Nobody came.

Father McKenzie,

Wiping the dirt from his hands as he walks from the grave;

No one was saved

All the lonely people (look at all the lonely people).

Where do they all come from?

All the lonely people (look at all the lonely people).

Where do they all belong?

Gary Allen 1936-1986 (None Dare Call It Conspiracy p. 73, 1971)

In the Bolshevik Revolution we see many of the same old faces that were responsible for creating the Federal Reserve System, initiating the graduated income tax, setting up the tax-free foundations and pushing us into WW I. However, if you conclude that this is anything but coincidental, your name will be immediately expunged from the Social Register.

Trevor Peacock 1931-2021 (“Mrs. Brown You’ve Got A Lovely Daughter” Herman’s Hermits single, 1965)

Mrs. Brown, you’ve got a lovely daughter.

Girls as sharp as her are somethin’ rare.

But it’s sad, she doesn’t love me now.

She’s made it clear enough; it ain’t no good to pine

She wants to return those things I bought her,

Tell her she can keep them just the same.

Things have changed, she doesn’t love me now.

She’s made it clear enough; it ain’t no good to pine.

Walkin’ about, even in a crowd, well

You’ll pick her out, makes a bloke, feel so proud!

If she finds that I’ve been ’round to see you (’round to see you),

Tell her that I’m well and feelin’ fine (feelin’ fine).

Don’t let on, don’t say she’s broke my heart;

I’d go down on my knees, but it’s no good to pine.

Mrs. Brown, you’ve got a lovely daughter (lovely daughter).

Mrs. Brown, you’ve got a lovely daughter (lovely daughter).

Mrs. Brown, you’ve got a lovely daughter (lovely daughter).

Andrew Klavan 1954- (“Shakespeare vs. the Transhumanists,” City Journal 2024)

The stories of both Lear and The Tempest are not only stories of fathers and daughters; they are dramas of inner struggle. The exiled and doomed Cordelia and the cherished and elevated Miranda are at once themselves and the symbolic animas of their fathers. Miranda’s marriage, in bringing together man and woman, also represents making one flesh of the male and female self. Marriage is theater, a performance in which yang and yin, will and surrender, power and creation, justice and mercy, meld into all that is required for full spiritual humanity. The transgenderism that materialist modern man seeks to accomplish with the bloody scalpel and the toxic syringe, the imagination allows us to fulfill completely with a man, a woman, and a wedding.

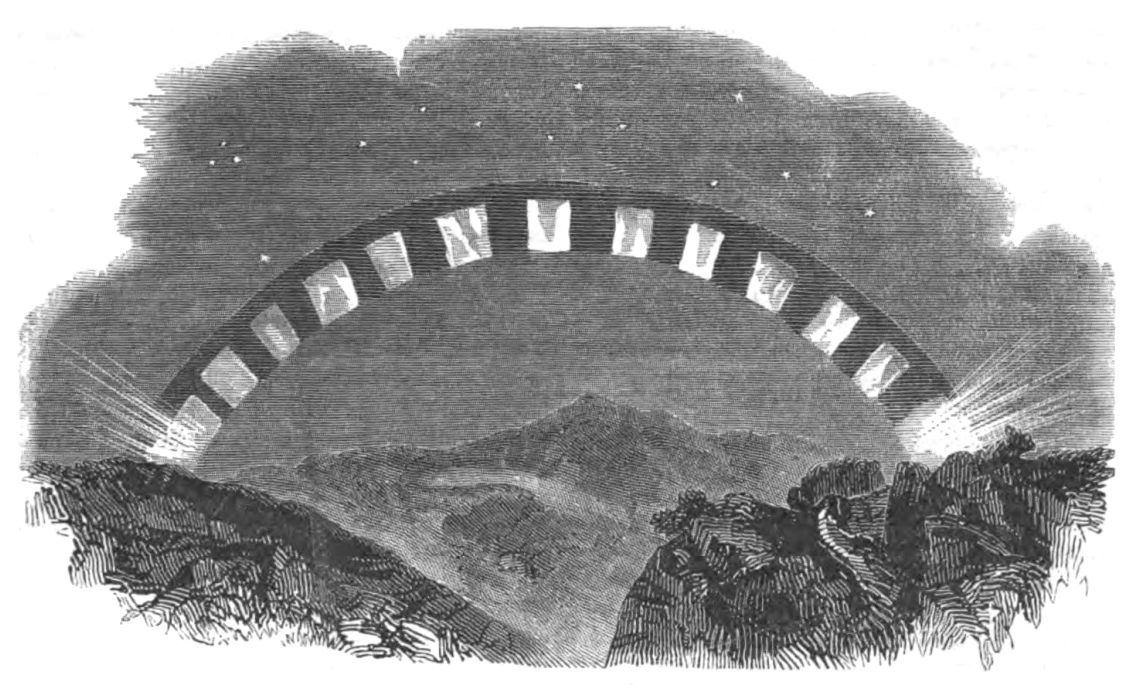

John Milton 1608-1674 (Paradise Lost Book 1)

The infernal Serpent; he it was whose guile,

Stirred up with envy and revenge, deceived

The mother of mankind, what time his pride

Had cast him out from Heaven, with all his host

Of rebel Angels, by whose aid, aspiring

To set himself in glory above his peers,

He trusted to have equalled the Most High,

If he opposed, and, with ambitious aim

Against the throne and monarchy of God,

Raised impious war in Heaven and battle proud,

With vain attempt. Him the Almighty Power

Hurled headlong flaming from the ethereal sky,

With hideous ruin and combustion, down

To bottomless perdition, there to dwell

In adamantine chains and penal fire,

Who durst defy the Omnipotent to arms.

Nine times the space that measures day and night

To mortal men, he, with his horrid crew,

Lay vanquished, rowling in the fiery gulf,

Confounded, though immortal.

Aristotle 384-322 (“Exhortation to Philosophy,” lost work by Aristotle, quoted in preface to The American Evasion of Philosophy by Cornell West, 1989)

If one must philosophize, then one must philosophize; and if one must not philosophize, then one must philosophize; in any case, therefore, one must philosophize. For if one must, then, given that Philosophy exists, we are in every way obliged to philosophize. And if one must not, in this case too we are obliged to inquire how it is possible for there to be no philosophy; and in inquiring we philosophize, for inquiry is the cause of Philosophy.

William Cullen Bryant 1794-1878 (“To the Evening Wind” passage quoted by Edgar Poe in The Southern Literary Messenger, 1837 in Edgar Allan Poe How To Know Him by C. Alphonso Smith, 1921)

Go—but the circle of eternal change,

Which is the life of Nature, shall restore,

With sounds and scents from all thy mighty range,

Thee to thy birth-place of the deep once more;

Sweet odors in the sea air, sweet and strange,

Shall tell the home-sick mariner of the shore,

And, listening to thy murmur, he shall deem

He hears the rustling leaf and running stream.

John Keats 1795-1821 (Letter, 10/9/1818, Selected Poetry and Letters, 1951)

The Genius of Poetry must work out its own salvation in a man: It cannot be matured by law and precept, but by sensation & watchfulness in itself. That which is creative must create itself—In Endymion, I leaped headlong into the Sea, and thereby have become better acquainted with the Soundings, the quicksands, & the rocks, than if I had stayed upon the green shore, and piped a silly pipe, and took tea & comfortable advice.

William Shakespeare 1554-1609 (Much Ado About Nothing Act 1 Scene 1 Benedick)

With anger, with sickness, or with hunger, not with love. Prove that I ever lose more blood with love than I will get again with drinking, pick out mine eyes with a ballad-maker’s pen and hang me up at the door of a brothel-house for the sign of a blind Cupid.

Michelangelo 1475-1564 (Com’esser, donna p.156 Life, Letters, and Poetry 1987)

Don’t you know, Vittoria, we must

at length, learn sweetness which endures

is but you, which the stone immures,

even as my own veins turns to dust?

Cause effects all, and everything adjusts

death to bright defeat. This my work ensures.

This is proven, lady, by my sculptures.

Art lives forever. Death forfeits its trust.

Eternity is, in colors or with stone,

in either form, spectacular for you and me,

as our resemblances devise.

A million years after we are gone,

art will find again my woe, your beauty

matched—and know my loving you was wise.

R.P. Blackmur 1904-1965 (The Double Agent p. 204 1935)

The poetry is the concrete—as concrete as the poet can make it—presentation of experience as emotion. If it is successful it is self-evident; it is subject neither to denial nor modification but only to the greater labour of recognition. To say again what we have been saying all along, that is why we can assent to matters in poetry the intellectual formulation of which would leave us cold or in opposition. Poetry can use all ideas; argument only the logically consistent. Mr. Eliot put it very well for readers of his own verse when he wrote for readers of Dante that you might distinguish understanding from belief. “I will not deny,” he says, “that it may be in practice easier for a Catholic to grasp the meaning, in many places, than for the ordinary agnostic; but that is not because the Catholic believes but because he has been instructed. It is a matter of knowledge and ignorance, not of belief or scepticism.”

John Crowe Ransom 1888-1974 (in The World’s Body p. 72 1938)

As for poetry, it seems to me a pity that its beauty should have to be cloistered and conventional, if it is “pure,” or teasing and evasive, if it is “obscure.” The union of beauty with goodness and truth has been common enough to be regarded as natural. It is the dissociation which is unnatural and painful.

George Graham 1813-1894 (Publisher quoted p. 118 in A Mystery of Mysteries: the Death and Life of Edgar Poe by Mark Dawidziak 2023)

Literature with him was religion; and he, its high priest, with a whip of scorpions scourged the money-changers from the temple. In all else, he had the docility and kind-heartedness of a child. No man was more quickly touched by kindness—none more prompt to return for an injury.